Target Usage: To manage a multi-person project on GitHub

Motivation: To manage a multi-person project on GitHub, one needs to know some additional project management features GitHub offers.

Lesson plan:

T10L1. Git Workflows covers that part.

T10L2. Forking Workflow (with Branching) covers that part.

T10L3. Other Project Management Features covers that part.

There are different Git-based workflows a project can use to manage code changes in a repo.

A Git workflow is essentially a set of agreed-upon rules that a development team uses to manage code changes and collaborate effectively on a project, answering questions such as: "How do we add a new feature without breaking the existing code?", and "When should we create a branch?". By having a consistent workflow, a team can proceed in an organized, predictable manner.

Workflows can be understood more easily by looking at two key dimensions that describe how they operate:

- D1:Collaboration model: who is allowed to push to the main repository?

- D1a:At one end of this dimension is the centralised model, in which all team members push to a single shared repository. The coordination is largely social: developers agree on rules about when and how to push.

- D1b:At the other end is the forking model, in which each contributor works in their own fork and proposes changes back to the original repository using pull requests. The maintainers of the upstream repository decide what gets merged. This model is common in open-source projects and large organisations because it scales well and provides strong control over what enters the main codebase.

- D1a:

- D2:Integration strategy: when and how often changes are merged into the main line of development?

- D2a:One end of this dimension is the feature-branch strategy, in which the work is done on branches that live for a relatively long time — often days or weeks. A feature is developed in isolation and only merged back when it is considered complete. Integration happens late, which can make merges larger and riskier, but the workflow feels intuitive and structured, especially when combined with pull requests and formal reviews.

- D2b:The opposite end is thetrunk-based strategy, in which there is a single main branch (the “trunk”), and changes are integrated to it continuously. Branches, if they exist at all, are very short-lived. Developers make small changes, merge them frequently, and rely on practices like automated testing and feature flags to keep the trunk stable and releasable at all times. In the simplest form of trunk-based development does not require branches at all; everyone commits directly to the main branch.

- D2a:

From these two dimensions, we get four representative workflow models that together cover the full landscape:

- Centralised + Feature-branch: a shared repository where developers create long-lived feature branches and merge them when the feature is ready.

- Centralised + Trunk-based: a shared repository with continuous integration into the main branch, possibly with no branches at all, or using short-term branches.

- Forking + Feature-branch: contributors work on feature branches in their own forks and submit pull requests when features are complete.

- Forking + Trunk-based: contributors work in forks but integrate small, frequent changes into the upstream trunk via pull requests (either using the main branch, or using short-term branches).

Many named workflows, such as Gitflow, are simply specific recipes built within one of these combinations rather than fundamentally new models.

A branch-based forking workflow is common in open-source projects and other large projects.

In a branch-based forking workflow, the official code lives in a designated 'main' repo, while each developer works in their own fork (hence, the name) and submits pull requests from separate branches (either long-lived branches or short term branches) back to the main repo. That is, it is a combination of the forking model and the feature-branch strategy. Not only this workflow is common for OSS projects and other large-team projects, it provides a good foundation for learning Git workflows (because other workflows are simpler than this, once you learn this workflow, it is easy to move to other workflows).

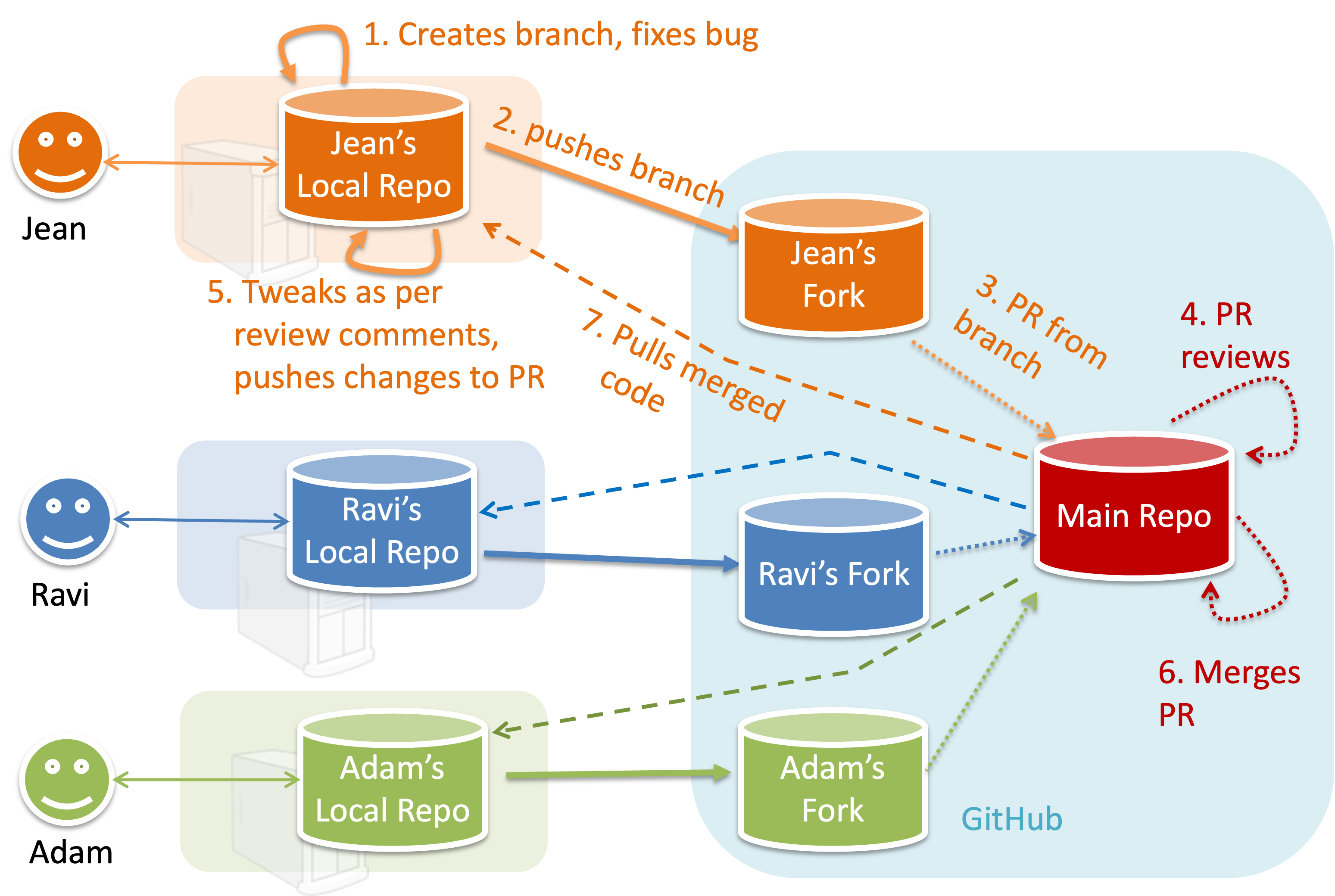

To illustrate how the workflow goes, let’s assume Jean wants to fix a bug in the code. Here are the steps:

- Jean creates a separate branch in her local repo and fixes the bug in that branch.

Common mistake: Doing the proposed changes in themainbranch -- if Jean does that, she will not be able to have more than one PR open at any time because any changes to themainbranch will be reflected in all open PRs. - Jean pushes the branch to her fork.

- Jean creates a pull request from that branch in her fork to the main repo.

- Other members review Jean’s pull request.

- If reviewers suggested any changes, Jean updates the PR accordingly.

- When reviewers are satisfied with the PR, one of the members (usually the team lead or a designated 'maintainer' of the main repo) merges the PR, which brings Jean’s code to the main repo.

- Other members (and Jean), realizing there is new code in the upstream repo, sync their forks with the new upstream repo (i.e., the main repo). This is done by pulling the new code to their own local repo and pushing the updated code to their own fork. If there are unmerged branches in the local repo, they can be updated too e.g., by merging the new

mainbranch to each of them.

Potential mistake: Creating another 'reverse' PR from the team repo to the team member's fork to sync the member's fork with the merged code. PRs are meant to go from downstream repos to upstream repos, not in the other direction.

One main benefit of this workflow is that it does not require most contributors to have write permissions to the main repository. Only those who are merging PRs need write permissions. The main drawback of this workflow is the extra overhead of sending everything through forks.

This practical is best done as a team.

Preparation One member: set up the team org and the team repo.

- 0.1)

Create a GitHub organization for your team, if you don't have one already. The org name is up to you. We'll refer to this organization as team org from now on.

- 0.2)

Add a team called

developersto your team org. - 0.3)

Add team members to the

developersteam. - 0.4)

Fork git-mastery/samplerepo-workflow-practice to your team org. We'll refer to this as the team repo.

- 0.5)

Add the forked repo to the

developersteam. Give write access.

1 Each team member: create PRs via own fork.

- 1.1)

Fork that repo from your team org to your own GitHub account.

- 1.2)

Create a branch named

add-{your name}-info(e.g.add-johnTan-info) in the local repo. - 1.3)

Add a file

yourName.mdinto themembersdirectory (e.g.,members/johnTan.md) containing some info about you into that branch. - 1.4)

Push that branch to your fork.

- 1.5)

Create a PR from that branch to the

mainbranch of the team repo.

2 For each PR: review, update, and merge.

- 2.1)

[A team member (not the PR author)] Review the PR by adding comments (can be just dummy comments).

- 2.2)

[PR author] Update the PR by pushing more commits to it, to simulate updating the PR based on review comments.

- 2.3)

[Another team member] Approve and merge the PR using the GitHub interface.

- 2.4)

[All members] Sync your local repo (and your fork) with upstream repo. In this case, your upstream repo is the repo in your team org.

- The basic mechanism for this has two steps (which you can do using Git CLI or any Git GUI):

(1) First, pull from the upstream repo -- this will update your clone with the latest code from the upstream repo.

If there are any unmerged branches in your local repo, you can update them too e.g., you can merge the newmainbranch to each of them.

(2) Then, push the updated branches to your fork. This will also update any PRs from your fork to the upstream repo. - Some alternatives mechanisms to achieve the same can be found in this GitHub help page.

If you are new to Git, we recommend that you use the above two-step mechanism instead, so that you get a better view of what's actually happening behind the scene.

- The basic mechanism for this has two steps (which you can do using Git CLI or any Git GUI):

3 Create conflicting PRs.

- 3.1)

[One member]: Update README: In the

mainbranch, remove John Doe and Jane Doe from theREADME.md, commit, and push to the main repo. - 3.2)

[Each team member] Create a PR to add yourself under the

Team Memberssection in theREADME.md. Use a new branch for the PR e.g.,add-johnTan-name.

4 Merge conflicting PRs one at a time. Before merging a PR, you’ll have to resolve conflicts.

- 4.1)

[Optional] A member can inform the PR author (by posting a comment) that there is a conflict in the PR.

- 4.2)

[PR author] Resolve the conflict locally:

- Pull the

mainbranch from the repo in your team org. - Merge the pulled

mainbranch to your PR branch. - Resolve the merge conflict that crops up during the merge.

- Push the updated PR branch to your fork.

- Pull the

- 4.3)

[Another member or the PR author]: Merge the de-conflicted PR: When GitHub does not indicate a conflict anymore, you can go ahead and merge the PR.

done!

RESOURCES

- A detailed explanation of the Forking Workflow - From Atlassian

GitHub provides many other features useful for managing a project.

Given below are some GitHub features that can be useful in managing projects hosted on GitHub.

Issue tracker for task-tracking: GitHub Issues is a lightweight task and bug tracker built into each repository, letting you create, assign, and discuss work in a structured way. Noteworthy features include labels for categorisation, assignees, issue templates and issue forms for consistent reporting, checklists, cross-references, mentions, and linking issues to pull requests, milestones, and projects.

Official docs: https://docs.github.com/en/issues/tracking-your-work-with-issues/about-issuesProjects for kanban-style task tracking: Building on top of the issue tracker, GitHub Projects provide flexible planning and tracking with tables/boards, custom fields, filters, and views, integrating issues and pull requests into a single workspace. Notable features include automation rules, insights, iterations, saved views, item fields (status, priority, estimates), and tight links to issues/PRs for end-to-end tracking.

Official docs: https://docs.github.com/en/issues/planning-and-tracking-with-projects/learning-about-projects/about-projectsMilestones: Milestones group related issues and pull requests under a shared goal or time frame, making it easier to track progress toward a release or sprint. You can set a due date, add a description, view progress by open/closed items, and filter issues/PRs by milestone; milestones also integrate with project boards and can improve planning and reporting.

Official docs: https://docs.github.com/en/issues/using-labels-and-milestones-to-track-work/about-milestonesReleases for managing product releases: Releases package a specific version of your software with tags, release notes, and optional build artifacts (binaries). Highlights include draft releases, pre-releases, auto-generated release notes, uploading assets, and associating releases with tags created via Git or the UI; they provide a clear history for users and downstream tooling.

Official docs: https://docs.github.com/en/repositories/releasing-projects-on-github/about-releasesGitHub Actions for continuous integration: GitHub Actions is integrated continuous integration and automation, running workflows on events like pushes and pull requests to test, build, and deploy code. Key concepts are workflows (YAML), jobs and steps, runners (GitHub-hosted or self-hosted), reusable actions from the Marketplace, caching, matrix builds, and environment/secrets management; status checks can be required before merging.

Official docs: https://docs.github.com/en/actions/learn-github-actions/understanding-github-actionsGitHub Pages for hosting a project website: GitHub Pages hosts static websites directly from your repository, ideal for documentation, portfolios, or project sites. You can publish from branches or /docs folders, use Jekyll for site generation, choose themes, configure custom domains and HTTPS, and automate publishing via Actions; it’s simple to set up and maintain alongside your code.

Official docs: https://docs.github.com/en/pages/getting-started-with-github-pages/about-github-pages

At this point: You are now able to use an appropriate workflow for your project, and also, make use of other project management features offered by GitHub.

What's next: This is the last of the Git-Mastery tours!